I gave a presentation today to the senior executive team at the NSW Department of Justice, led by Secretary Andrew Cappie-Wood.

These are the notes I used for the talk on seven public sector trends.

Framing 1

The first frame reinforces the fact that the work of government is changing. The public sector has been gradually changing into the “public purpose” sector. Not that the public sector, in its traditional institutional form, isn’t still important and distinct. But more of the outcomes we want from those engaged in public work are co-produced in working conditions that are increasingly connected, collaborative and porous.

There is a new premium on legibility, which is not the same as transparency (which is always important). People don’t just want to see what’s going on, but at least at some level want to know why.

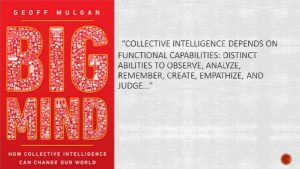

Finally, collective intelligence will be the dominant mode of most public work. The ability to convene and sustain more complex “assemblies” of multiple and distributed intelligence (platforms, knowledge, expertise, resources) will be a rising function of government.

Framing 2

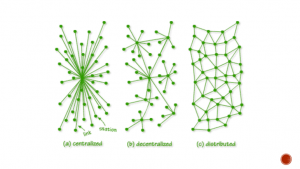

We live in a world trying to respond to the rhythms and potential of distributed networking with organisations and institutions still largely hostage to the constraints and habits of centralised or, at best, decentralised structures and culture.

As Paul Baran recommended in his seminal report for the Rand Corporation about ways the US could withstand a strike by the Soviet Union on American communications networks, distributed networking offered a mix of resilience and distributed power.

Much of the promise, and many of the pitfalls, of public sector reform are grounded in the clashing instincts and behaviours of these three ways of seeing the world – centralised, decentralised and distributed.

Working out which makes most sense for different tasks and contexts – they all have a role to play at some point and for some conditions – is a leadership task in itself.

Again that backdrop, these are seven public sector trends I have noticed or been directly engaged with over recent times.

1 Digital transformation: are we there yet

The digital transformation of government is at an interesting stage. We have made undoubted progress using digital tools and platforms to improve many of the more transactional dimensions of government.

The focus has largely been on convenience, speed and efficiency. There has been less progress is three key areas – the application of digital tools and culture to the policy making, using digital platforms and capabilities to accelerate and deepen a larger open government agenda and improving citizen engagement by making government more legible.

The next stage of the digital transformation process will explore the relationship between digital capability, the changing role of government and new ways of working across the public sector.

2 Design: Fad or Future

The use of design in government is poised between a passing fad and a serious addition to the tool box of modern public administration.

On the fad side of the equation is the risk that the alluring legitimacy of co-creation and engagement with customers (the heart of good design) remains an attractive ad- on to relatively unchanged instincts for top down control and authority.

On the more positive side of the equation is the emerging evidence that, at least in some cases, design is being used to question and change many of the unhelpful instincts of policy and service design that routinely fail to reflect the impact on, and value for, those whose lives they are intended to improve.

[Extract from a chapter I have written for an upcoming publication from the University of Melbourne on design in the public sector]

“The rise of design and design thinking in the public service reflects a growing realisation that many of the risks and opportunities that communities and governments face can’t be dealt with using many of the traditional tools and processes available to public servants and agencies.

The risks and opportunities have become more complex and interconnected, the power of government to create service and policy responses is diluted by an array of contending players and interests and “policymakers typically find themselves working with less time, trust and money to achieve their goals.”

Many of the traditional tools and processes in the public sector, which tend to privilege predictability, control and distinct roles and accountabilities, struggle to engage challenges whose dynamics are fluid, interconnected and unpredictable.”

3 The renewal of trust

Trust is leaking from the institutions of government (and a lot of other institutions too) at an alarming rate. From Donald Trump to the royal commissions on child sexual abuse and banking, the evidence seems increasingly to suggest many public, private and civic institutions are out of touch and out of shape.

There are things that institutions can do to rescue trust. Being more open and honest, communicating directly and consistently with stakeholders and responding to their concerns, becoming not just more transparent but more legible are all things institutions can do right now. Royal commissions are institutional investments in greater legibility. That’s why they can be so time consuming, forensic and often painful in their insights and implications.

There is nothing inevitable about the decline of trust and there is some evidence, including the 2018 Edelman Trust Barometer report, that we have not lost our interest in knowledge and expertise. When we find it, we respect it. But it has to be respectful, authentic and ethical. The renewal of trust is a fixable proposition. The public sector is especially well placed to contribute to, and in some cases lead.

It’s worth reinforcing, picking up on the work of someone like Andy Haldane in the UK, the Deputy Governor of the Bank of England, that the work of trust rebuilding is neither spectacular nor quick. Its arc is long and patient and relies primarily on the daily habits of clear thinking and honest public servants and their leaders.

4 Confusion about commissioning

The language of commissioning has become both more pervasive and more familiar. It isn’t clear whether its practice (a bit like the current fate of design) has shifted from convenient label and relatively superficial lip service to deeper and more substantial practice.

The promise of commissioning is palpable. It offers the prospect of a more discerning conversation about the best way to achieve policy, regulatory and service delivery outcomes. And, in the process, it engages a challenging discussion about what those outcomes are or should be in the first place.

The risk is that, in the clash between an instinct to commission and some of the traditional requirements of procurement, procurement wins. Commissioning, rightly understood and done well, will have a profound impact on the culture and performance of the public service if it is allowed to work properly and if Ministers and public servants are prepared to invest some hard work, courage and authority in its evolution and spread.

5 Collective intelligence assemblies

The speed, intensity and complexity of many of the risks and opportunities that government is trying to resolve are putting government and the public sector to the test. They are making new demands on our ability to combine the best available skills, expertise and resources – inside government and outside in the business, academic and community sectors – and point that collective firepower at the right place to achieve deep system shift.

There are some examples where “assemblies” of collective intelligence are helping difficult problems that impact big areas of our lives like health, social care, education and cities.

But too often, the collaborative instincts of collective intelligence run counter to many of the cultural and institutional practices of public policy. This is how Geoff Mulgan put it in 2006 [Good and Bad Power: The Betrayals and Ideals of Government 2007]

“They require openness to the unexpected, the time it takes to become immersed in and conversant with a complex system, familiarity with many disciplines, and the mental toughness needed to escape the tyranny of the status quo. They require counterbalances to the tactical and contingent – the fear of leaks that crushes honest debate, the insecurity that prevents rigorous self-scrutiny and the wishful thinking that prefers not to contemplate unpleasant possibilities.” (My emphasis)

6 Bringing policy and delivery back together again

The last 30 years of public sector reform, under the influence broadly of “new public management”, have driven a substantial wedge between policy and delivery, between ‘thinking’ and ‘doing’ in policy and services. It’s becoming obvious that divide has made it harder to solve the problems we want to solve and achieve the outcomes that people want.

If we want solutions that are simpler, more integrated, durable and responsive to people and context, we will need to find ways to reconnect policy making and delivery.

Delivery people need to be in the room from the start of the policy process, not kept out until the policy people have finished their elegant (or not so elegant) designs and then thrown them, as it were, over the fence in the hope that the delivery folks will somehow work out how to make it work out.

In particular, policy systems will have to confront the possibility that some of the most important and valuable information needed for good policy making is to be found at the “moment of truth” interactions with frontline staff, customers and citizens. Failre to close the policy-delivery gap is not just unhelpful, it ends up creating a policy process that risks becoming inefficient, foolish and disrespectful.

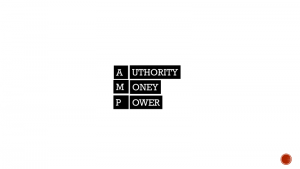

7 Solving problems, changing systems: a question of AMP

There is an inverse relationship between the rising rhetoric around system change and any evidence that systems are actually changing.

We know that many of the big systems we engage every day – education and learning, welfare, child protection, the criminal justice system, transport, food and agriculture for example – are struggling to adapt to new performance demands in a world characterised by speed, intensity, connectedness and a thirst for legibility.

They are being asked to swap “scalable efficiency” for “scalable learning”. [John Hagel reference] They are also being asked to think more deeply about whether or not the way we address the individual elements in a larger system (the “pieces”), which is often driven by short-term demands for “results” and a political fix, undermines our ability to make larger system (the “puzzle”) work more effectively.

What that requires is a longer view of “what works” and some patient institutional and political that can understand and adjust to the system’s complexity and unpredictability.

There are plenty of people trying to tackle the challenge of system change.

Success will be difficult but not impossible. It will be a function of time to stop long enough to think about the long term, invest in some open and honest mutual (and highly collaborative) learning and a willingness to contemplate, and then act to achieve, new flows of authority, money and power.

Generally speaking, if those three things are not flowing differently, systems aren’t changing.

A really excellent and thought-provoking post, Martin. I wholeheartedly endorse all your points, especially ‘public purpose’ and (I’ll come back to it) the importance, potential, and risks of commissioning.

I just want to draw attention to a couple of points I think worth considering:

“There is a new premium on legibility, which is not the same as transparency (which is always important). People don’t just want to see what’s going on, but at least at some level want to know why.”

On the whole I agree (though I am always sceptical of ‘new’ – I bet we could see this in previous decades if we looked). But we should be aware of the risks and costs of ‘legibility’ – see Seeing like a State and the symbolically important story of the ‘normalbaum’. Sometimes legibility (demanded by the state, because the state acts rationally, and how can you have rationality without legibility?) destroys the living, ecosystemic nature of what is being looked at: https://model.report/s/z7wn6e/the_normalbaum

You are talking of course about people asking for justification – perhaps my point is really referring to the additional challenges that will be faced by commissioners and leaders acting systemically, when they can’t necessarily account for their actions at a detailed, legible way?

There’s another good example here: https://stream.syscoi.com/2018/05/01/improvement-legibility-ecosystems-and-change/

So in that context, I think it’s interesting you chose that particular word, legibility (which obviously triggers me!), compared to e.g. engagement, involvement, being part of… and that comes from a paradigm of the citizen being outside and separate from the ecosystem of public service – usually the victim or the Poor Sick Miserable Person being Helped – sometimes the scrutiniser and person who holds the system to account (makes the public service tell its story). Each side of this coin, I think, is actually an imposter. As long as this separation remains, your challenges will be irresoluble, I think. We can generate ‘enough trust’ for the problems to simmer under, enough collective intelligence and learning to get by – but we won’t be tapping into the real deep wells that might come from seeing citizens and public services as integral parts of the same system.

I came here because I very strongly agree about the potential of commissioning – and the risks you highlight seem accurate. Perhaps it’s worth closing by saying that if commissioning is cast in the same paradigm as we traditionally talk about ‘policy’ – i.e. entirely rational, legible, separated from citizens and with authority, money, and power operating in traditional ways – we will inevitably fall back into the same problems.

Great insights Benjamin…Seeing Like a State is one of my favourite books:)

I am probably guilty of using legibility in a loose or at least very particular way. I completely agree that one notion of legibility links closely to the thirst for rationality and faux order which is really all about power that Scott skewers so uncomfortably.

But my intention was to use legibility in its more literal and literary sense, the sense that something is legible if you can read it, make out the words and therefore make sense of what the words mean. It is that kind of legibility I am groping towards.

In contrast to transparency, which simply allow you to see, legibility, at least in the conception I am reaching for, allows you to read and understand, to get some sense of what is happening and why.

It strikes me that much of the decline in trust in institutions is their stubborn illegibility born of an era which, as I note from Andy Haldane’s comments about the Bank of England, didn’t have to worry about such matters.

Well, now we do and many of our institutions simply don’t know how to respond or how to balance a proper response to being more readable with some measure of requisite confidentiality and discretion.

Thinks for the input. Much appreciated

The public sector and officialdom need to remember what they are there for which is to provide services to people within a country:

–Efficiently

–To a consistent standard

–At the lowest possible cost consistent with that consistent standard bearing in mind what other more advanced countries have and are achieving

–Without making excuses for non delivery

–Speedily

–In a manner which is is consistent with a public service ethos which is concerned with producing results which are consistent with an ethos of making things better for the consumers of those services

–In a manner which embodies commonsense rather than legalistic exceptions and procedures

–In a manner which is fully decision treed and costed across all forseeable parameters so that the consequences of service delivery in 1 area do not create problems in others or in emergent areas

–In a manner which does not create opportunities for fraud,bad unintended consequences or trouble.

–With full accountability for both strategic and operational delivery ,something that is not happening with Chief Constables and Police and Crime Commissioners with the latter being an unnecessary burden on taxpayers

–In an adaptable way consistent with agility of delivery and responsiveness to demand

–Without creating failure demand and drivers to “gaming the system”.

–Using simple language–I understand the post but a great many people who are products of an inadequate state education system would not

That’s a pretty good list! I especially like the reference to “failure demand”, which I think is a much overlooked and misunderstood dimension of public service design which often seeks efficiency and impact in ways that will have exactly the opposite effect.

Interesting article and it is good to read that we are all trying to learn about how to do public service better.

In my limited knowledge – I have been working to understand and transform public services for 14 years, I have some evidence and thoughts about what you have written about the UK.

Our health system has been designed to be managed functionally – completely at odds with the evidence that shows that although some of medical treatments can be seen that way, the majority of workflows operate across these functions. The result is that there is huge amounts of rework in the workflows, and that integrated approaches to service users is almost impossible. The system of referrals is highly disfunctional.

With public services there is a clear distinction between central gov services, and local ones. I would agree that Design Thinking has and will continue to make a considerable boost to highly transactional services – passport issue, etc. However, Design Thinking principles are starting to demonstrate they have the ability to make greater inroads in other services – the work is still to mature to that level here in the UK.

As for Digitalisation by default. That is all very well, but it is recognised that Digital is not the solution for those who are in need, and/ or have significant complexity in their lives. Whilst the number sin any area if low, they consume the greatest amount of resource. The way that these members of the public get best served is through services which can adapt to their complexity and individual variation. This has been shown time and time again, and it is through personal engagement that this occurs – not through standard services.

Lastly, the trend is certainly towards collaborative working and knowledge sharing, locality, and person centred design. Commissioning, by its intent and design, does not easily fit into this model. This is especially true when we realise that ‘services’ does not just mean a service, it means working with people in highly flexible ways that are driven by what matters to that person. I have worked with commissioned services, and they all tend to be operated in ways that are counter to what public services need to work. The idea that commissioning brings in private sector efficiency is correct in one way – but this result is only proven if the evidence is gathered that treats each demand as a unit, an accountants view of the world. The real world outcome of commissioned services has little evidence to show that it can stand up to a well managed and run public service.

The ‘commissioning mindset’ of functionalisation its problematic in the public sector. As an example, if we take housing allocations and the implementation of Choice Based Lettings in England, this has proven to be a system that is not designed to solve the problem we have. The waste it produces is matched by the poor outcomes it generates for those society is trying to help – and it fails them in most cases (80%). If CBL is removed, and those in need are attended to individually 80% are helped and costs are reduced.

Interesting article and it is good to read that we are all trying to learn about how to do public service better.

In my limited knowledge – I have been working to understand and transform public services for 14 years, I have some evidence and thoughts about what you have written about the UK.

Our health system has been designed to be managed functionally – completely at odds with the evidence that shows that although some of medical treatments can be seen that way, the majority of workflows operate across these functions. The result is that there is huge amounts of rework in the workflows, and that integrated approaches to service users is almost impossible. The system of referrals is highly disfunctional.

With public services there is a clear distinction between central gov services, and local ones. I would agree that Design Thinking has and will continue to make a considerable boost to highly transactional services – passport issue, etc. However, Design Thinking principles are starting to demonstrate they have the ability to make greater inroads in other services – the work is still to mature to that level here in the UK. Design Thinking is by no means a fad, it has been around and proven itself in the private sector – and is the basis for a new type of change method and management style.

As for Digitalisation by default. That is all very well, but it is recognised that Digital is not the solution for designing services for those who are in need, and/ or have significant complexity in their lives. Whilst the percentage of such demands in any area if low, they consume the greatest amount of resource. The way that these members of the public get best served is through collaborative services which can adapt to their complexity and individual variation. This has been shown time and time again, and it is through personal engagement that this occurs – not through standard services.

Lastly, the trend is certainly towards collaborative working and knowledge sharing, locality, and person centred design. Commissioning, by its intent and design, does not easily fit into this model. This is especially true when we realise that ‘services’ does not just mean a service, it means working with people in highly flexible ways that are driven by what matters to that person. I have worked with commissioned services, and they all tend to be operated in ways that are counter to what public services need to work. The idea that commissioning brings in private sector efficiency is correct in one way – but this result is only proven if the evidence is gathered that treats each demand as a unit, an accountants view of the world. The real world outcome of commissioned services has little evidence to show that it can stand up to a well managed and run public service.

Our experiment with Universal Credit – which is a flawed design, cannot work correctly, and is hugely wasteful compared to the system it has replaced. It cannot absorb the variation in its demands types, failed to realise that many people who need its service are also leading chaotic lives, and it cannot collaborate with other public agencies.

This ‘commissioning mindset’ of functionalisation and economies of scale is problematic in the public sector. As another example, if we take housing allocations and the implementation of Choice Based Lettings in England, this has proven to be a system that is not designed to solve the problem we have. The waste it produces is matched by the poor outcomes it generates for those society is trying to help – and it fails them in most cases – 20% helped. If CBL is removed, and those in need are attended to individually 80% are helped and costs are reduced.

Some great observations here John, especially the tension between reforms designed to improve productivity and efficiency, I guess, and the persistent reality that, at least at the margins but perhaps more extensively than that, there are people and problems that need a more personal approach.

It reminds me of the work of John Seddon and his systems approach that shows us that doing the job well first time, and properly attending to the nuance and complexity of each person’s situation, ends up being more effective and cheaper (largely through the reduction of what he calls “failure demand”…additional work generated by failing to get it right first time).

Also, do you know Gary Sturgess’ work on commissioning? Well worth exploring and with some powerful framing and insights about what commissioning could be contributing if it was done well and moved beyond contracting or outsourcing.