Screens and social media addictions are changing, perhaps irreparably damaging our brains.

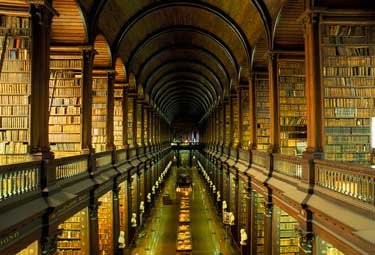

It’s a view often associated with Susan Greenfield, the British peer, scientist and brain expert who, as I recall at one lecture I heard her give, pits “people of the book” against “people of the screen”.

Shorter attention spans, an unwillingness or incapability to engage longer, more persistent expositions of complex ideas, distracted by an addiction to (digital) distraction. As we go digital, we’re losing our minds. This is a link to her book Mind Game, whose sub title presumably tells its story – “how digital technologies are leaving their mark on our brains”.

Baroness Greenfield is not alone.

Here’s a summary of a longer article (which I haven’t yet read – perhaps that’s a worrying sign?) – on the same topic. The article, by Cristine Rosen, asks these questions:

- Will the book be around much longer?

- What will become of the book and its related print culture?

- Will “collaborative ‘information foraging’ replace solitary deep reading”?

- Will “the connected screen will replace the disconnected book”?

- Does regular reading truly benefit our society?

- Are print literacy and screen literacy complementary capacities or just competitors?

- Will a new reading class develop?

- Should we be the master or the student when we read?

- “What exactly is reading?”

- Are screen readers more “users” or “consumers” and not “readers”

- What can e-books do better than printed books?

And the piece concludes with this baleful reflection:

If reading has a history, it might also have an end. It is far too soon to tell when that end might come, and how the shift from print literacy to digital literacy will transform the “reading brain” and the culture that has so long supported it. Echoes will linger, as they do today from the distant past: audio books are merely a more individualistic and technologically sophisticated version of the old practice of reading aloud.

But we are coming to see the book as a hindrance, a retrograde technology that doesn’t suit the times. Its inanimacy now renders it less compelling than the eye-catching screen. It doesn’t actively do anything for us. In our eagerness to upgrade or replace the book, we try to make reading easier, more convenient, more entertaining—forgetting that reading is also supposed to encourage us to challenge ourselves and to search for deeper meaning.

The most recent example of this debate I came across is from Niall Ferguson, who in an interview in the Weekend Australian during his recent visit to Sydney made the link between the declining engagement with long texts and the decline of civilisation itself:

“If you are on Facebook, Twitter and WeChat and WHatsApp, constantly communicating with your contemporaries, which seems to be the norm, you’re not reading War and Peace. You really can’t read anything long.

I think there has been a collapse of serious reading among a generation of my students who are cut off from the great works of world literature. How can we possibly preserve our civilisation if the next generation has read 1 per cent of why we read? They are in danger of being cut off from the great truths of the human condition by their own incessant chatter with one another.”

If we’re inexorably launched on the digital era, which we are, then it matters a lot if, as a consequence, we’re losing something big and important that is foundational to our ability to engage, share, transmit and evolve foundations of culture.

I am a baby boomer and, as I often do in these matters, find myself uncomfortably these sharp distinctions of binary reassurance (someone must be right, someone must be wrong).

As someone who, for pleasure and for academic necessity, has read War and Peace, and lots of Dickens novels, Thomas Hardy, Thomas Mann, Paradise Lost, lots of Shakespeare plays and the occasional tome of history and philosophy, I kind of get the angst. It bothers me.

But I am also a happy digital migrant to a world of surprise, speed, synthesis and speculation which, for all of its predictably human capacity for venal, narcissistic crap has a breathtaking ability to unlock whole universes of knowledge I wouldn’t otherwise even know about, much less understand.

So here are my questions the answers to which I ponder regularly but not conclusively.

- If you haven’t, or don’t want to, read War and Peace, is that a problem?

- Is digital culture – which, even if book people might not accept it, is adding to human culture in its own right by creating and sharing new insights and treatments of human experience and knowledge – valid and equal to the kind of culture that demands extended periods of reading paper-based texts?

- Creating stuff digitally – websites, blogs, software, new platforms and tools like blockchain technology – demands persistence and concentration too. Even the dreaded Twitter and Facebook, icons of terminal distraction to the book-inclined, reward a certain type of persistence, engagement and even concentration.

- What’s the minimum that is needed to be part of a common culture in terms of what people have read or been exposed to? (I barely studied Latin at school, have never studied ancient Greek and have only a superficial grasp of the “classics” that someone like John Milton or the average, well-educated school boy in the 17th and 18th century would have taken for granted; is that a problem, or is my lack of a working knowledge of Ovid or Thucydides a kind of cultural haemorrhage?)

- Can you be cultured without a sufficient working knowledge of the “canon” of western culture? But maybe you now can’t be cultured without a sufficient working knowledge of the digital world and how it works?

- Is the inability to read long texts a sign of an inability to concentrate for long periods, or is it a sign of an unwillingness to concentrate for long period in that particular way? And does that matter?

The point in the end, presumably, is to provide the widest possible access for the largest number of people to the best that human knowledge, ingenuity and imagination has to offer that throws some light on the human condition and what it means to lead a good, generous and useful life.

What that entails, how we learn and engage that knowledge and its requisite habits of mind will always change. That’s not necessarily a bad thing.

If it’s true that digital culture is making it impossible for us to bring the necessary habits of work and cognition to these tasks, that is a problem. But I’m not sure it is. I imagine there have been lazy and distracted students at every age in history.

And I suspect every era’s version of distraction and disruption from the received norms of cultural practice and engagement have changed the way our brains and habits of learning work. And they’ve doubtless generated similar combinations of angst and fury (my grandfather thought television was the work of the devil and assumed that my brother and I would be irreparably damaged if we spent too much time with Dr Who, or Top of the Pops).

I’m not sure it matters as much as those who say it matters think it matters. Or maybe I just don’t want to admit it matters that much.

Leave a Reply