I had one of those interesting collisions between a couple of strands of my work last week that helped to make sense of a couple of things.

One piece of work is The Possibility Partnership. More about this below but it’s a project full of, well, possibility about making a dent in the vexed question about why so much of the effort and angst our human services systems invest in trying to shift conditions for those experiencing entrenched and complex disadvantage isn’t working and may even be making things worse.

The second strand is my continuing investment in the patient slog that is public sector and public policy reform, in this case informed by following the work of Jennifer Pahlka. Her recent book is a must-read and her collection of Substack essays on Eating Policy (as in “delivery eats policy for breakfast” – think Michael Lewis and The Fifth Risk) are required reading in my research and intelligence gathering.

Again, more below but the point here is her latest insights into why it’s wrong that so often the policy making machine in government – the place where the rules of the game are set and changed – finds it so hard to see, hear and absorb the wit and wisdom of those actually playing the game. Their unique perspective on whether or not the rules are working as intended you would think would be welcomed as gold by the rule setters. No such luck; and thereby hangs this tale.

A big part of the policy and public sector reform game is becoming The increasingly pressing need to find better ways for the rule-making process in government (consisting primarily of developing policy, determining funding, designing commissioning and directing evaluation) to recognise, validate and actually use the knowledge of ordinary people – citizens and their communities and those on the front line of public service delivery.

And to be clear, this is not an arcane piece of obscure wonkery. It is that, of course but it’s very much more.

To the extent that the biggest threat to democracy, itself perhaps the single biggest challenge we face in a world full of plenty of other big challenges, is its inability, real or perceived, to deliver results that make sense to people and make a palpable difference to the lives they want to lead, then one of the single biggest factors is the almost pathological inability of the rule making process to hear, listen to and then act on the evidence that keeps coming up from the ground about how things could be done better and why.

Too often that knowledge is missed or ignored. After a while, people get fed up and frustrated. Then they give up trying and just get angry. Then you get Donald Trump. A little cartoonish, but basically true. That’s what’s at stake here.

Putting that another way, if we got better at this ‘connecting middle’ piece, we’d likely get a whole lot better at delivering things people want and need where and how they want and need them and making sure people don’t feel ignored or expendable. And that would be a substantial deposit in the “strengthening democracy” account to rescue trust and confidence in democracy and the potential of good government done well.

The Possibility Partnership

There are two recurring mantras you often hear when you talk with people engaged in the front-line work of service delivery across our human services systems (and it’s a pattern too in other big policy systems I suspect).

One is the mantra that claims, backed by equal parts unmissable evidence and steadily mounting frustration, solutions and good practice pioneered in a specific location and which would be valuable to others in the system almost never get picked up, absorbed and then spread as a new dimension of performance for the whole system. Or at least that process if it does happen is slow, clunky and riven with obstacles and barriers.

And the other thing you hear is the complaint that when good results offer evidence that people are being helped to live lives they value, it happens in spite of and not because of the system. In other words, good work too often demands the rules be bent, broken or ignored. Generally speaking, that is a clue that the system isn’t working.

The reason is simple.

Great results “on the ground” often struggle to be seen much less absorbed into business-as-usual design and practices at the point where policies, rules and guidelines are made. And just as much, innovations that emerge from the people and places who are “in the rules” are often not translated effectively into day-to-day practice.

We seem to be stuck. And getting unstuck is hard.

Enter The Possibility Partnership.

The Partnership is a sector-led, multi-partner and growing collaboration between community services organisations, government, philanthropy and business.

Its ambition is to change the purpose and practice of Australia’s human services system, so everyone, especially people and communities experiencing complex and entrenched disadvantage, can live the lives they value.

The Partnership concentrates on this specific point of intervention in a systems innovation and leadership approach – improving the way knowledge, expertise and real progress “on the ground” can influence and change the way the rules of the system are made and changed.

It’s trying to do something about what happens at the ‘meet in the middle’ moment, convening people from the “ground”, in the “rules” and whole bunch in between, based on deep listening, co-creating solutions and driving action.

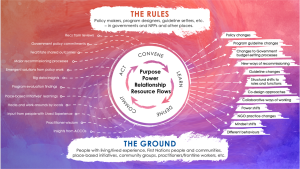

The diagram is a pretty good mud map of the idea. At its heart are the ‘four keys’ of system change – purpose, power, relationship and resources. More on that another time.

The proposition is that we can find better ways for these pieces to come together to make more consistently useful and productive puzzles that fuel real system shift for better results people can see and feel. And that work “in the middle” is the work of shifting the conditions that lead to current usually poor or sub-optimal system outcomes.

Stop Telling Constituents They Are Wrong

Jennifer Pahlka is an astute and experienced analyst and a seasoned practitioner of the art and science of good government. Not so much at the grand philosophical level, although that as well, but more at the operational level of government programs and policies and the way the civil service actually works or doesn’t.

Like all good philosophers of government, she matches insight and wisdom with a good set of scars on her back and on the backs of those tough, patient toilers in the vineyard of good delivery and practice whose work she admires and chronicles.

She deals in the rhythms of public service culture and practice that too often get missed in the Big Debates about government and democracy. And that’s especially true in the lead up to Trump 2.0, especially the likely trajectory of the Musk/Ramaswamy trillion dollar assault on the Washington bureaucracy about which she has been offering some very sensible and calm advice here and here for example.

But what caught my eye last week was this piece.

At first glance, the advice to “stop telling constituents they’re wrong” is a short essay on the arcane, even trivial. The piece picks up “a little dust up” about the interpretation of the regulations that permit the handling of fresh fruit, specifically oranges and bananas, in US childcare facilities. If you’re into short stories about the way little pieces of bureaucratic ambiguity shine an uncomfortable light on the meaning of life and the universe, read it in full.

The burden of the story is whether or not the regulations require a facility to have at least six sinks in their kitchen to be able to handle fresh fruit. The ‘spat’ is not just about what the regs say or don’t say, but how the regs land when they slide off the antiseptic page of the regulator’s drafting table and confront the messy reality of life in a childcare centre. How can they fill their menus with fresh fruit and veg without having the resources to provide the kind of ‘robust’ kitchen infrastructure the regs seem to imply.

In Pahlka’s telling, the real question isn’t what the regs say or don’t say, but the impact the regs end up having:

But the debate of whether [the regulations] are pro-fruit or anti-fruit misses the point. If daycares end up serving bags of chips instead of bananas, that’s the impact they’ve had. Maybe you could blame all sorts of folks for misinterpreting the regs, or applying them too strictly, or maybe you couldn’t. It doesn’t matter. This happens all the time in government, where policy makers and policy enforcers insist that the negative effects of the words they write don’t matter because that’s not how they intended them.

And further, if that is indeed the perverse consequence of the clash between the regulations as drafted and the regulations as ‘landed’, then THAT information should be vital intel for the next round of regulation.

After all, we’re supposed to be in a world, where experimentation, rapid feedback and some agility in turning what’s been learned into something better in subsequent iterations (of policy, regulation, services or whatever) is now the main game.

But too often that’s not how it’s being played (‘digital era” ways of working, anyone?). And it’s not happening because to play it that way requires the whole process to be open to that kind of knowledge and learning process in the first place.

But the real insight in Pahlka’s little gem of an essay is far from trivial.

Quoting the small business owner in question, Pahlka skewers the real problem – the disconnect between policy and experience, between the people who write and draft and the people who have to live with that is written and drafted:

As a small business owner, I’ve seen this disconnect before, a disconnect between what laws make for good reading on paper and what laws would make for good policy in the real world. And I think a key part of this disconnect, illustrated by the pushback I got when I started asking about the sinks, is this ingrained disregard for working people by policy makers in DC. They did not take input from someone working in a daycare seriously, and that’s wrong.

Just to be clear, I’m not arguing (and as far as I know neither are Jennifer Pahlka or the people tangled in this little policy ticket) that the disconnect between policy and practice is itself the problem (although it’s obviously part of the problem).

The real problem is that, in the terms that The Possibility Partnership has adopted, ‘the rules’ can’t or won’t listen to ‘the ground’. A settled, robust process of collaborative, generative learning that ought to be the engine of good policy and effective regulation isn’t there or isn’t working.

The connecting middle

How do we get ‘the rules’ to hear, listen to, validate and then absorb the wisdom and knowledge ‘on the ground’, where that is useful and relevant, so that the larger system gets to steadily improve through better and more reliable models of collective learning and shared intelligence?

That’s Pahkla’s punchline. And that’s the simple, but difficult purpose of The Possibility Partnertship.

It might not feel like it but spending some time and effort solving that dilemma would do wonders to close the policy-implementation gap and make a major investment in lifting trust and legitimacy in the process. And not just, I would argue, in the human services systems but pretty much anywhere government policy and services engage with people and communities. Which is pretty much everywhere. This is a big and pervasive problems and unlocking this part of it could have big and pervasive (and very positive) consequences.

It would mobilise a process of systemic, collective learning that listened to and heard what people ‘on the ground’ had to say as part of a predictable and widely agreed way to turn that knowledge and experience into better rules.

If we can crack this code, everyone wins … better delivery for results people want, rising levels of trust and respect for a process of learning and improvement that reeks of legitimacy and care and, in the case of The Possibility Partnership, a human services system more likely to be doing the right thing by those it most wants to serve and support because of the way it works, not despite its persistent disconnections.

Addendum Good Government and the Assault on The State

Two final reflections.

This work is as much about the future of a strong and effective democracy as it is about making the machinery of modern government work better. In fact, there’s a good argument that the former relies consequentially on the latter.

According to this take, failure to attend to the machinery improvement bit risks becoming part of a much larger and deeply troubling assault on the state:

Much ink has been spilled on the threat of democratic erosion … But defending the modern state is also vital for preserving democracy. From protecting civil rights to counting the votes, it’s hard to imagine a stable democratic future without the machinery of modern government.

The Assault on the State: How the Global Attack on Modern Government Endangers Our Future Stephen E Hanson Jeffrey S Kopstein Polity 2024 p13

Some years ago, Geoff Mulgan wrote a book explaining why and how good government done well was a gift that needed to be nurtured and appreciated more than perhaps it often is.

This is how he made the case:

Good government is one of the very best things that can happen to any society. Contrary to conventional wisdom…the business of government is becoming more moral, not less;. Many governments are stumbling closer to an ideal of service that has been imagined for as long as states have existed but was rarely realised;…and just as new knowledge has given governments vastly greater power, it has also made them more dependent, more accountable and more embedded in their societies. Bit good government is always fragile, always vulnerable to capture by special interests and self-serving elites and always at risk of becoming detached from the people it is meant to serve and from ideals

Good and Bad Power The Ideals and Betrayals of Government Geoff Mulgan Allen Lane 2006

More moral, an ideal of service? Right now that feels a little like the triumph of hope over experience. But an aspiration worth hanging onto. Because, if we don’t, the outcome will have stern consequences for us all.

Leave a Reply