There’s a couple of lines of argument about how we do public policy in this country (and in other comparable countries for that matter) that have been on my mind recently.

One line is that we’re no good at it. Or at least not as good at it now as we once were in a golden age often associated with the era in which those opining the decline were active and influential.

Lost our policy “chops”

According to this line of thinking, for a number of reasons (of which more in a minute), we’ve lost our policy “chops” and live in a period when the normal sources of good policy making, especially within the public sector at all levels, seem to be withering.

The second line of argument is that the policy making we are doing suffers from a terminal lack of discipline and good process, leading to outcomes whose quality and lack of deep, often reforming impact is a reflection of the haphazard and superficial manner in which too much of it has been thrown together.

Taken together, the arguments contend that we are living with the consequences of a steady decline in the art and practice of policy making.

For some, the steady decline in policy capability in the public service at every level is the inevitably consequence of a prolong period of financial and ideological hostility.

Austerity, efficiency dividends and other ostensible budget repair mechanisms, teamed with a growing disposition to see the public sector in Reaganesque terms as part of the problem, not part of the solution have eroded talent for, and interest in, good policy

In its stead, the argument concludes, we’ve copped the baleful consequences of issues management, terminal spin and knee-jerk political reactions whose ambitions barely reach and rarely last beyond the headlines they are designed to manipulate.

Another explanation is social media and the digitally-hyped media “cyclone” of 24×7 commentary and contributions whose speed and intensity is often remarked to be in inverse proportion to its depth and value. Cacophonous crowds of barely-informed and noisy opinions crowd into the public space which has lost the capacity and aptitude for “slow thinking”, discernment and good judgement.

And a third line of argument is that policy making has become a more contested space. Complaints about a decline in the quality and capability of policy making inside the pubic service is at least partly a function, this argument goes, of the steady rise outside, including from a much richer mix of advisors and consultants in different domains – business, universities, think tanks and the rest, both here and around the world.

In a world in which access to great thinking and analysis pretty much from anywhere and everyone, including the globally best and brightest, is available instantly and without too much effort, it’s not surprising that the quality of the local contribution can seem less impressive or influential.

By this line, people (often former public servants) complain about the demise of good policy making in the public service in slightly sniffy tones that betray a concern that they no longer have the territory quite as much to themselves as they once might have done.

What makes for good policy?

These were all in my mind this last week as I spent a day with a bunch of public servants in Brisbane discussing policy making, the role of evidence and the importance of courage and persistence in pursuit of influence for good policy.

The discussions were part of a “masterclass’ for the current cohort in the DG Forum, a leadership and talent development program devised by James Purtill, Director General of the Queensland Department of Natural Resources, Mines and Energy (DNRME). I helped to design and facilitate three of the “tutorial” forums during 2018, the last of which was held in Brisbane last week.

It’s a great initiative and a clever way to combine leadership succession planning in the department with nurturing a range of policy and leadership skills across a large, complex and highly distributed government agency.

We talked about a lot of the factors that bear on the bigger questions of what makes for good policy, drawing on the ability to draw on deep sources of influence for great outcomes. Oddly, many of them started with the letter “C”:

Cabinet – understanding the disparate and often contending personal, ideological and political make-up of Ministers, not all of whom are necessarily always on the same side, is a pretty important starting point. Influence, analysis and good advice must be tailored to the actual terrain on which you are working.

Campaigning – good policy rarely happens by dint of sharp intellectual analysis alone; it never hurts to be technically proficient of course, but good policy demands the skills and patience of good campaigning, a mixture of strategy, street-wise tactical astuteness, patience and persistence, the ability to persuade and a deep commitment to. and comfort with, creative opportunism.

Contest – expect a contest for pretty much every aspect of the policy process, from its inception and founding arguments about public interest and need through to options for success and often highly divergent paths from idea to strategy to execution. And expect the contest to come from inside government, across the bureaucracy and with and from those outside the public service with interests, expertise and influence of their own to burnish and peddle.

Communication – no policy work is done well if it isn’t done according to some pretty exacting rules of good communication – clarity, simplicity, repetition, good argument and counter-argument, doggedness, respect and sometimes a good dose of humility (even if that has to be faked).

Courage – when policy engages complex and contested ideas and values, which is almost always, getting a result requires courage on the part of the public service and politicians; copping criticism and sometimes personal abuse, the ability to keep arguing the public interest or a long-term frame of reference when all around are baying for a “do something” response that privileges speed and simplicity over quality and deep impact.

Craft – putting all of these elements together – intellect, cunning, campaigning, strategic opportunism, courage – serves as a reminder that doing policy well is more a craft that a science, a set of instincts and capabilities best improved more by doing than by theory and always honed by layers of ambition tempered by patient practice and persistent learning.

Collaboration – little is done in the policy game any more (if it ever was) alone; heroic individualism is out. Like good innovation, good policy is a team sport; but like all team sports, it can get and look pretty ugly, remembering as I learned somewhere along the track that “collaboration is an unnatural act between non-consenting adults”.

The Wiltshire 10

The work with DNRME coincided with another project on which I have played a small part, led by former NSW Treasury Secretary Percy Allen as a project of the newDemocracy Foundation.

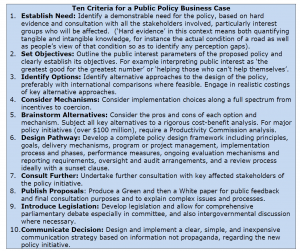

The project, designed to explore whether it is possible to arrive at an agreed conception of what good policy making looks like, asked two ideologically opposed think tanks – Per Capita and the Institute of Public Affairs – to assess 20 recent policy decisions by the Federal, NSW, Queensland and Victorian Governments against the 10 precepts of good policy process developed by QUT Professor of Public Administration Ken Wiltshire.

This press release explains the process and outcomes of the project in some detail and points to other links to find out more.

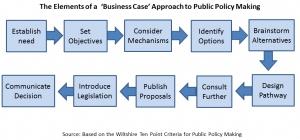

The 10 principles are set out below

As Ken reinforced in our discussions (we were both members of the small editorial committee that reviewed the two think tank reports as they took shape), these are insights that emerge from over 30 years’ study and practice of policy making here and around the world.

These are the principles explained in more detail

Like all lists, it is neither a representation of the real world nor does it suggest that the list works like a list – linear, simple and sequential. But there is an assumption that the model works best if the 10 elements do follow some kind or order and pattern.

For example, “establishing need” needs to be somewhere close to the start of the process or at least the idea of need, being clear quite what the policy is trying to do and why, needs to be at the heart of the process.

Need, intention and clarity of purpose, though, aren’t always things that are crystal clear at the start and often have an emergent quality. Often, a policy process is driven by an instinct for “better” or the desire to solve a problem without knowing exactly the parameters of the dilemma or even a sharp sense of what “better” might be or look like.

There’s a focus on “green” and “white” papers as part of the process which, for some, will sound a bit old fashioned. I’m not sure we’ve seen so much recently of that approach.

But the idea of setting out a case or a set of propositions essentially in draft form for debate and discussion (the “green” paper process) to be followed by a firmer set of proposals and decisions after the discussion (the “white paper” piece) remains important and can often be done by other means.

There’s a focus in the principles on communication and collaboration and a salutary reminder of the importance of a rigorous search for options that need to be tested and checked within the framework of a comprehensive framework for the policy “campaign”.

It’s a strong list of the pieces that, all other things being equal, are more likely than not to lead to a good outcome if all of them, with some rigour and determination, are reflected in the policy process.

And that’s, broadly, the conclusion that the newDemocracy project came to.

The IPA and Per Capita assessments landed on much the same assessment of those of the 20 policy projects deemed to be have been done well, including the Victorian Voluntary Assisted Dying Law and the Queensland Legalising Ride-sharing apps and those that came up short including the creation of ‘Home Affairs’ department, the NSW local council mergers and the Queensland vegetation management law.

Working with these principles, and reflecting on them in the light of the discussions in Queensland with DNRME ‘s rising leaders, I found myself with these additional reflections:

What impact on these kinds of principles do the speed and intensity of the contemporary environment, fuelled by social media and faster, more dense connections of influence and communication, have on both the intent and process implied in the principles?

What’s the best way to understand the relationship between process and outcome in the policy game? Does good policy lead to good outcomes? Can you get a good policy outcome from a poor process that follows few of the principles but might instead by the outcome of opportunism, luck and the persistence of a few strong-willed people determined to get a result?

Many of the principles imply highly contested questions about how they are determined, by whom and on what conditions. So “establishing need” begs big questions about whose version of “need” gets to prevail and on what terms. How widely and creatively options and alternatives are sought implies big questions about authority and influence and who gets to decide what options gets to be in the mix and which are excluded.

I wondered too at various stages of the project about the impact of new models of policy making influenced by the contemporary interest in human-centred design, design thinking and open innovation.

The design ethic is not linear. It starts with the inkling of an idea or sense of “better” and then moves straight to what the experience of “better” might be from the perspective of those intended to be impacted by the design, not by the designers. The point is to evolve a sense of better, and then to design a solution that combines simplicity, elegance and feasibility, with users embedded n every stage of the process. That isn’t always the way policy processes I am familiar with tend to work. To what extent does a more overtly design-based model of policy making upend some of these principles or at least offer a different conception of how each of them is undertaken and how, and in what order, they come together?

Six attributes

For all of that, though, it’s hard to argue the purpose, provenance and potential of the 10 principles as a statement of some basic good practice for policy making. And it’s hard, too, not to agree with the underlying premise of the newDemocracy project that, too often in recent times, we have witnessed policy processes the poorer for not reflecting at least some of these ideas.

Partly as a function of the project, and tested further in the discussions with the DNRME policy forum, I’ve drawn together six attributes of good policy making.

Could we argue that good policy is more likely than not to emerge from a process in which:

- All available evidence is assembled and reviewed, made easily available, widely shared and widely and openly debated

- There is a high degree of (appropriate) openness and transparency from the start of the process

- An eclectic mix of people have a chance to shape the policy debate, including how and whether the debate is put on the agenda in the first place

- The widest mix of expertise, including especially the expertise of experience and close-to-the-ground exposure to the issues and implications being debated in the policy process, is engaged and given a fair chance to make their contribution

- Considerable effort is invested in establishing the facts and evidence on which the policy debate will be undertaken, including where that evidence is contested and unsettled

- A clear sense of what constitutes a good outcome emerges together with a sharp sense of what the public interest is or should be and, again, how the contesting views about those core issues are being heard and debated.

What does seem clear is that good policy is always a matter of authority, power, influence, skill, speed and judgement.

The interesting question is how current and emerging conditions, not the least being the rise of new forms of digitally-infused and data-charged knowledge and analysis, is changing the way in which those attributes work.

Whatever might be the best way to define and practice good policy making, it’s as well to keep in mind that, as this tribute to US public administration scholar and writer James Q Wilson points out, we’re talking here about unsettled institutions using imperfect knowledge to solve problems about whose causes and conditions we are usually uncertain:

The inconvenient truth is that frequently our knowledge of how to get to the source of what afflicts the economy or the polity, and then to fix it reliably, is woefully fallible. Correctives are confidently bandied about, but too often — and often too late — they get mugged by reality.

P.S. The link to the press release that promises more information does not appear to work. The project is exciting in bringing together the two parties with divergent ideology to come to agreement at the process level. I’d like to read more about this inspiring project, if you could advise the best places to look, please. Ta, Pamela.

Let me check and see what I can do