If there is a talent crisis in the public sector, which I think there is and about which I wrote something in a recent post you can find here, the question is begged what is the mix of talent that the public service of the future needs?

It turns out that there’s a fair bit of recent work on that topic. These are some reports which I’m going to write about briefly over the next few weeks:

1

This report – “core skills for public sector innovation” – is from the OECD earlier this year: https://www.oecd.org/media/oecdorg/satellitesites/opsi/contents/files/OECD_OPSI-core_skills_for_public_sector_innovation-201704.pdf

2

This report from the OECD – “skills for a high performing civil service” – was also published this year https://www.oecd.org/gov/pem/Skills-Highlights.pdf

3

The 21st century public servant, jointly authored by Helen Dickinson and Helen Sullivan and published by the School of Government at the University of Melbourne http://bespoke-production.s3.amazonaws.com/msog/assets/b7/d2ec80db6d11e58244af312943873d/MSoG-21c-Draft2_2_.pdf

Blog by one of the authors, Helen Dickinson https://21stcenturypublicservant.wordpress.com/tag/melbourne-school-of-government/; an article in The Mandarin by former UK Cabinet Secretary Gus O’Donnell in response to the report https://www.themandarin.com.au/10851-lord-gus-odonnellleadership-and-reform-in-the-public-sector-a-tale-of-two-countries/?pgnc=1;

4

A report from the UN Development Program – “work in the public service of the future” – published in 2015 (I think; many of these publications seems to be unusually shy about their publication date). http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/capacity-development/English/Singapore%20Centre/WorkingPaper_Work-PS-Future.pdf

5

This report from Canadian researcher Mark Jarvis – Creating a high performance public service against a backdrop of disruptive change – was published in July 2016 https://mowatcentre.ca/wp-content/uploads/publications/122_creating_a_high-performing_canadian_civil_service.pdf

6

There has been some interesting pieces of work from the UK too, including the 2012 Civil Service from 2012 https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/305148/Civil-Service-Reform-Plan-final.pdf and there have been a series of pieces from the Institute for Government since then looking at different aspects of the civil service “transformation” strategy.

So the idea is to look at each one of these reports and (a) summarise their insights and prescriptions to get a sense what they feel the public service of the future should look like, talent-wise and (b) pick out some of the common themes, and perhaps some uncommon ones too, from across these different takes on the questions of talent and see what that might add up to.

The OECD on innovation skills

The OECD report on innovation skills throws an interesting light, both direct and indirect, on a series of assumptions about what kinds of talent we can expect the public or civil service to be seeking and nurturing.

The report rehearses the process by which the OECD evolved a framework, partly with the help of Nesta in the UK, an initial framework of 40 attributes associated with the innovation skills and competencies which at that stage (May 2016) were grouped into five broad areas, including rules and processes, people, knowledge and ways of working.

As part of the work, Nesta developed a set of skills “profiles” for innovation specialists who are brought in from outside to work in government on a range of innovation roles. I’ll come back to those profiles later.

The guts of the OECD work is a 6-skill profile of innovation “talent” that a “modern 21st century public service” should expect. These skills might not be necessary in all officials all the time, but the report argues that “all officials should have at least some level of awareness of these six areas in order to support increased levels of innovation in the public sector.” (page 8)

These are the six skills:

- Iteration: incrementally and experimentally developing policies, products and services

- Data literacy: ensuring decisions are data-driven and that data isn’t an after thought

- User centricity: public services should be focussed on solving and servicing user needs

- Curiosity: seeking out and trying new ideas or ways of working

- Storytelling: explaining change in a way that builds support

- Insurgency: challenging the status quo and working with unusual partners

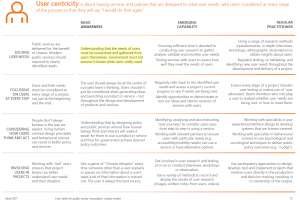

This is how the model looks diagrammatically, which I think helps to reinforce the sense in which the six elements feed off and into each other. That create the sense that in their combination is a kind of diamantine strength which makes the model especially appealing in many ways.

The report then outlines each of the 6 skill areas according to a frame that combines what they describe as four elements of practice:

- Managing innovation projects

- Using prototypes to explore approaches

- Conducting tests and experiments

- Taking risks, but not with time and money

…and setting those again three levels of capability:

- Basic awareness

- Emerging capability

- Regular practitioner.

So, for example, the detailed presentation of the “user centricity” skill domain looks like this:

These are just the summary paragraphs on each of the six attributes from the report to give you an idea of the way in which each is defined and positioned:

Iteration

Iteration is about the incremental and progressive development of a project. It is most commonly associated with modern software development practices where new features or updates to functionality are released when they are ready, rather than a “big bang” approach that releases a large number of new/updated features at the same time. Iteration skills aren’t just about project management, using prototypes and conducting experiments can also be considered part of iterative practice.

Data literary

The world has been experiencing a data revolution in recent years, yet it is widely held that government is not making the best use of the data it produces or has access to. The nature of the data is also changing: there is an ever greater and increasing volume, velocity and variety of data available. Alongside traditional analytical professions (statisticians, economists, researchers) a new type of activity and occupation (‘data science’ and the ‘data scientist‘) has emerged from individuals who are able to exploit these new forms of data.

User centricity

The idea of involving citizens in developing public services is not new, and “customer focus” has been mantra of management consultancies for decades. However, the arrival of the digital government agenda, and the subsequent bottom-up development of new online services has placed the idea of “user needs” at the focal point of both policy making and service design – in both the US and the UK, user needs are the first principle of government guidelines for developing digital public services.

Curiosity

Innovation in the public sector is about introducing new and improved products, services, ways of working to deliver better outcomes for citizens and improved operational efficiency. Therefore, curiosity and thinking creatively are part of the essential life blood of innovation – they are the action of finding out new things. Many people will say “I’m not creative”, but everybody has the capacity and ability to be creative.

Story telling

Stories have been a part of human culture since the dawn of language. Storytelling can be used by leaders and others within organisations in a number of ways: to explain who you are, to teach lessons, to outline the future, and to inspire action in others. Change in the public sector is no longer about moving from static state A to static state B, instead change is a constant companion – changing operating environments, changing expectations, changing user needs.

Insurgency

Innovators in government are sometimes seen as internal ‘insurgents’ or ‘rebels’, working to change the usual way of doing things. If curiosity is the part of the lifeblood of innovation that is how we identify new things, then insurgency is about making those new things happen. Public servants are often typecast risk averse – and often with good reason if they are a prison officer or regulate nuclear power plants – however, the number of situations where an official must not be doing something because of a risk of direct harm to citizens or national security is relatively small.

So what does this all mean for the talent question?

The talent assumptions behind these attributes seem to be to include at least these:

- A public service in which “curiosity” and “insurgency” are recognised as key skills for innovation will expect public servants, at least some of them, some of the time, to be defiant, counter-cultural or at least counter-intuitive and be adept at the art and practice of asking for forgiveness, not asking for permission. The talent to work “against the grain” in pursuit of an idea that you think is worth pursuing, but which will be resisted by those, including in positions of power and authority, because it will challenge the way things have always been done, will be in high demand.

- We can expect these attributes to accelerate the growth across the public sector of a pervasive culture of design and design thinking. The combination of “curiosity” and “user centricity” implies public servants adept in, and comfortable with, the rhythms and values of designers, especially privileging the restless, almost anthropological obsession with users and customers, willing to start all policy and service design problems with seeing, truly seeing, the lives and contexts of people and places.

- Public servants capable of telling stories implies another rich and complex strand of the emerging talent mix. Now, it seems, the traditional and often superficial reflexes of “comms” – some press releases, a web site, a bit of social media – will be supplanted by the ability to tell a compelling story about the big arcs of change, as well as the smaller swirls of improvement and reform, that people will need to understand if they are going to be brought along for the ride.

- An innovation package that requires “iteration” and “curiosity” implies a talent for persistence, persistence and agility which, consistent with the software development world from which these ideas emanate, tends to a sensible mix of speed, intensity, flexibility and collaborative discernment.

Two things came through for me from the OECD 6-atttibute model.

Firstly, I like the attributes.

The idea of a public service of the future whose people and organisations are suffused with a mix of curiosity, insurgency, a willingness to privilege users and their real lives and the ability to weave convincing stories around emerging narratives for change and reform strikes me as a fine ambition.

The framework offers a tantalising glimpse into a public service in which I imagine many of us would be proud and eager to serve.

But the second thought that struck me as I read the report was just how realistic is it to assume this kind of framework either can navigate the difficult (treacherous?) journey from compelling OECD report to the cultural and professional lived experience of every day public servants?

Here I am less sanguine.

Because what I see, hear and encounter too often in the public service is evidence that a mixture of ideology, political constraint, poor leadership and a tough and sometimes unforgiving media (social and ‘normal’) environment renders it very hard, perhaps sometimes impossible, save for the most determined or the unusually lucky, to put some of these attributes into action.

How often, for example, have I heard agencies espouse the virtues of customer-centricity but persistently display the behaviour of almost “customer-blindness” when it comes to designing programs and services and rolling them out in ways which seem to either ignore or misunderstand what users and citizens and customers want and need?

When was the last time you were in a public sector agency, or worked in one yourself, where there was a palpable sense that “insurgency” – the willingness to go against the grain, call out the inadequacies of the status quo and try something different, even if it offends current architectures of power and status – was tolerated or even positively sanctioned by leaders willing to trade some of their personal and professional capital to offer you that privilege?

And we keep hearing the talk about agility and speed – the need to iterate and learn fast through ‘good’ failure – but encounter too often resistance to the practical implications of those attributes, especially as you edge closer to some of the big systems of public work like procurement and recruitment.

Actually, I can think of a few examples where I could probably sense at least some these attributes at work, which is a good thing and a sign that perhaps we need not be too baleful about the real-world prospects for the “OECD Six”.

But my general point is that these kinds of previews of the likely talent profiles for a future public service too often seem stranded on the shores of a kind of “counsel of perfection” in which all real-world constraints and obstacles have mysteriously evaporated.

I really don’t think, for example, it ought any more to be acceptable for public sector reform documents, or individual agencies, to espouse concepts like “user-centricity” or “insurgency” without fronting up to the scepticism, perhaps even cynicism, with which such terms frankly ought now to be loaded. I think we’re all too far down the track of hearing, but not necessarily seeing these ideas play out to be expected to read a report like this and assume that the translation of the advice into day-to-day action is as trouble-free as the reports appear to assume.

In fact, the report does pick up one dimension of this theory-to-action dilemma when it calls out the central part that leadership, or its absence, plays in determining the extent to which talent in the public sector is liberated or buried.

The report notes:

Alongside specific skills that enable public sector innovation, our research has identified that mind-set, attitudes and behaviours can be just as important as specific hard or soft skills in enabling innovation within the public sector. Beyond the focus of individual skills and capabilities many research participants and stakeholders have highlighted a number of other organisational factors that are also crucial for increasing levels of innovation in the public sector. In particular, leadership capability, organisational culture and corporate functions/systems (finance, HR, IT, legal) that are enablers of innovation not ‘blockers’. While outside the scope of the skills model, these are important factors that need to be considered in operationalising/implementing the skills model and achieving higher levels of innovation in the public sector.

I added the emphasis in that quote – “while outside the scope of the skills model”.

Well, that’s a problem, isn’t it?

The misalignment between these kinds of talent virtues and the environment in which they are expected to be deployed – culture, systems, and especially leadership – is very much THE point I would have thought. The point being there is little to be gained by waxing lyrical and even inspirational about a bunch of attributes you think should characterise the work and culture of a modern public service if the surrounding organisational and institutional context is anathema to those same attributes.

To repeat a thought I’ve written about before, it’s possible that the real talent “problem” for the future of the public service is not its absence, but its more or less wilful misuse and mistreatment by those responsible for managing the organisational contexts and systems that will make or break its potential value and impact.

In subsequent blogs, I’ll look at the other reports I mentioned at the start and see what light they shed on the central question of the likely or necessary talent mix required for the public service of the future.

That will build up an interesting composite picture over the different reports that will offer some strong signals about the challenge for talent in the public service of the future – do we have enough of these talented people, where can we find more, how do we recruit, retain and reward them (and do we have to recruit them all in the traditional way anyway, given new patterns of work, worker and workplace) and are we doing enough to truly disrupt some of the unhelpful contextual antibodies whose individual and combined impact is too often is to snuff out its true potential?

Note

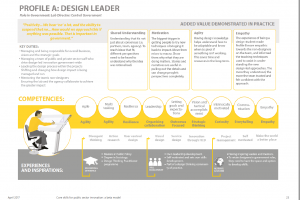

The chart below, just as an illustration of the more detailed work in this report by Nesta, is a example of one of the 8 innovator in government profiles complied by Nesta as part of their work for the OECD.

The charts repay more detailed analysis.

These are the 8 profiles covered in the Nesta work – design leader, design-led project manager, design methods lead, methods expert (delivery), methods expert (educator), data business leader, data business developer, methods expert (deliver,

Leave a Reply