I wrote a piece recently looking at an OECD report that proffered six attributes of future public servants in a world that is becoming more connected, complex and (sometimes) confusing. These were the six -iteration, data literacy, user centricity, curiosity, storytelling and (a personal favourite) insurgency.

This time I’m looking at a couple of linked pieces of work about what it means to be a “21st century public servant”. One comes from the University of Birmingham in the UK and the other from Melbourne University’s School of Government. They are now a few years old but both pieces of work illuminate some more of the thinking about the talent base for a future public service and about the context of change from which their prescriptions emerge.

The Australian research was kicked off by a 2012 discussion paper, jointly prepared by the School of Government at Melbourne University and the Victorian Department of Premier and Cabinet.

The paper starts where most of these pieces of work start, sensibly enough, which is with the context and environment in which the whole idea of a new set of skills, and their talent implications, for public servants starts to make sense.

In 2012, the context included “the impact of globalisation, changing citizen expectations and technological change,” combining to create “a different environment for the public service of the 21st century.” Policy advice has become more contestable from multiple new sources, co-production and the more intense engagement with citizens and service users is shifting from mantra to practice and new digital tools offer the promise, if not always the performance, of reinvigorated democratic engagement.

And these changes, in turn, “give rise to a new skill set that sits alongside the traditional skills expected from a public servant.”

The implication is a public service anxious to reshape from “the rigid bureaucracies of the early 20th century” towards what we’re now beginning to see as a familiar litany of “the new” – a more agile and flexible public service, with a more diffuse, open and collaborative way of working.

In the discussion paper, the question was whether incremental change was going to be enough (probably not) and whether the public service would be up to the task of, quoting a piece of work from the UK, “an altogether bolder approach…focused on searching out, incubating, and sustaining much more radical and game-changing innovation’

The paper then draws on some work by Gartner to identify the “new world of work” implications for the public service. It is a litany that, even though it is now 5 years old, is both familiar and helpful as a quick summary of the kind of work-world in which the 21st century public servant might be expected to be confident, capable and creative:

Gartner has forecast key changes to the world of work through to 2020. The public service will not be immune from these trends which include:

- the emergence of non-routine where the value that people add is in the non-routine, analytical or interactive rather than automated processes and tasks

- teamwork will be valued and rewarded and will occur more frequently

- the prevalence of spontaneous work

- simulation and experimentation, which will require engaging with the frontline or walking in the shoes of users.

The discussion paper then calls out four themes that it argues underpin the broader roles of the 21st century public service:

- Collaboration: relationships between people and organisations

- Communication: with an emphasis on digital media modes

- Commercialisation: getting the best value from public, private and community sectors

- Control: ensuring legal, financial and democratic standards are met.

These themes are drawn from another UK report, jointly prepared by the University of Birmingham and the think tank Demos, called When Tomorrow Comes: The Future of Local Public Services. The report presents the work of a Policy Commission that worked between 2010 and 2012 to examine in some depth the likely shape and work of local public services in the UK.

The link here is Helen Sullivan who came across from Birmingham to head the School of Government at the University of Melbourne (and is now the head of the Crawford School of Public Policy at the Australian National University.)

Some important “C” words there, not the least “commercialisation”, recognising the increasingly urgent need for a new kind of literacy in the public sector to do with more complex bundles of private and public value, and “control”, a kind of bedrock public work attribute – rigour and high levels of administrative hygiene.

Another “C” word – commissioning – gets a significant mention too as part of the shifting context within which specific skills and capabilities are required to maximise efficiency, public value and long-term service reform. The report calls out the work of Gary Sturgess especially in a couple of reports, here and here, that have become standard references for the commissioning debate including calling out the difference between commissioning and contracting out. They are neither synonyms nor inevitable staging posts on the continuum of service reform options.

In another list – there are plenty of lists of skills and capabilities for the “public servant of the future” or the “public service of the future” – the Melbourne paper draws on these ten “future workforce” skills for the public service:

- Sense-making: getting to the deeper meaning or significance of what is being communicated

- Social intelligence: relating to others deeply and directly

- Adaptive thinking: thinking and generating solutions outside of the norm to respond to unexpected and unique situations

- Cross-cultural competency: operating in unfamiliar cultural settings and using differences for innovation

- Computational thinking: translating large amounts of data into useful concepts and understanding data-based reasoning

- New-media literacy: leveraging new-media forms to communicate persuasively

- Transdisciplinary: understanding concepts across different disciplines to solve complex problems

- Design mindset: designing tasks, processes and work environments to produce desired outcomes

- Cognitive load management: filtering important information from the ‘noise’ and using new tools to expand mental functioning abilities

- Virtual collaboration: working productively with others across virtual distances

Not very much missing there.

Actually, it’s an impressive list.

Any list of future skills attributes for public servants is impressive that includes “social intelligence” (especially important, it strikes me, if we are to improve the context-specific approach to policy making that pulls policy and delivery much closer together), “transdisciplinary”, which might even now be too modest as we start to think about “trans-contextual” work, and then “design mindset”. Just those three on their own represent a pretty demanding talent trifecta.

If you stop and think about those ten skills for a moment, and then do a quick check in your own mind how well you would assess the current public sector is doing on gathering and growing the requisite talent those attributes imply, you get a glimpse into the necessary scope and ambition that I think needs to infuse our answers to the “question of talent” in the public service of the future.

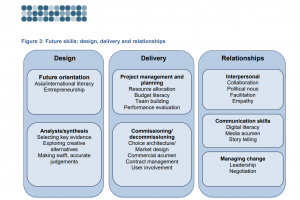

The paper draws all of that together into a framework under three headings – design, delivery and relationships. Under each, there are distinct capabilities defined, each of which bring with them considerable talent requirements in their own right. The diagram below is from the discussion paper:

Later, the Melbourne paper talks about the four priorities that the UK’s 2013 capability plan for the civil service built its prescriptions around:

- Leading and managing change

- Commercial skills, including skills to undertake commercial transactions such as commissioning services from the private and voluntary sectors

- Delivering projects and programs

- Redesigning services and delivering them digitally.

There are some big themes emerging from studies like these, at least in my mind.

The persistent values and capabilities of public work – rigour, impartiality, ethics, fairness, a care for and pursuit of the public or common interest, a concern for the long term – are now mixed with aspirations for a new set of “traditional” skills that, in the future, will be just as valuable for effective public servants – innovation and the ability to think beyond the usual, a capacity for speed and agility, the capacity to lead whole systems and curate complex communities of skills and expertise to achieve big public results – better health, skills for work, safer and “smarter” cities, climate adaptation – that can no longer be “delivered” in a simple or singular production model.

Public servants will be expected to be more commercial or finance-savvy as well as much more nuanced in the blend of thinking and doing – or policy and delivery – from which better results and longer-lasting impact will invariably derive.

And all of this within the context of increasingly volatile landscape of political and community opinion and, at least by some assessments, a policy environment that has grown timid, constrained and increasingly willing to confuse spin and style with substance and sustained, difficult analysis, debate and trade-offs.

What does it mean to be a 2st century public servant?

The UK report on which the University of Melbourne work drew had the same focus on the 21st century public servant.

It asked the same basic question – what does it mean to be a 21st Century public servant? What are the skills, attributes and values which effective public servants will display in the future? How can people working in public services be supported to get those skills?

Its context, sketched early in the report, is pretty much the same. Public services are going through “major changes” in response to a range of issues such as “cuts to budgets, increased localisation, greater demands for service user voice and control, increased public expectations and a mixed economy of welfare provision.”

The report argues that, contrary to the popular notion that public servants live and work in the public sector, and especially in the context of what it describes as “the increasingly mixed economies of welfare,” many who have public service roles “work for for-profit or not-for-profit organisations outside of the public sector.”

In other words, and in an important addition to the debate, the report effectively calls out the reality of a “public purpose” sector. This is a concept I first came across many years ago in the work of American sociologist Lisbeth Schorr. In one of her books, she notes almost as a throwaway line that it had become increasingly misleading to see the results and impact that policy was trying to have as a function simply of the work of the public sector (and, by inference, of the work of formally defined and specifically employed public or civil servants.) She used the phrase “public purpose” sector to describe what she argued then should be a new focus for capability and investment.

Although hardly a new phenomenon even then, and certainly not now, the idea that the question of talent for the future of the public service has to embrace people and institutions inside and outside its formal institutional boundaries is important Not only do we need to think about answers to the talent question in terms of the talent we need both inside and outside the public sector – in the more broadly defined “public purpose” sector – but we need to think too about the specific talent mix that is required to lead, manage and work in, across and between the different domains that make up the public purpose sector. Public purpose sector leadership is itself a rising talent requirement of a modern public service.

Back to the UK report.

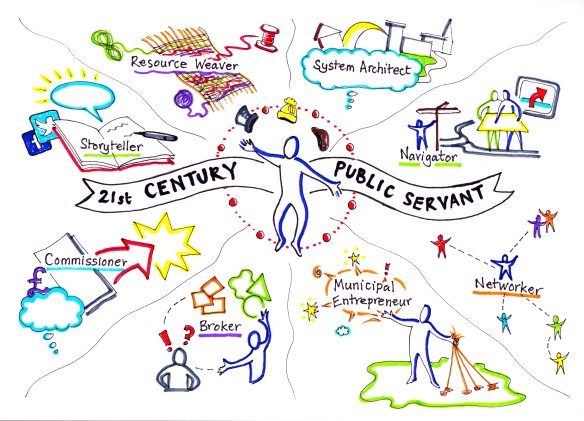

It concluded that some of the new roles that will be taking up the work (and talents) of public servants in the future included story-teller, resource weaver, systems architect and navigator. Storytelling and navigating are both skills which betray the increasingly complex and networked environments within which we will expect public servants in the future to work with confidence and impact. Concepts like “weaving” and “navigating” imply complex contours, multiple players and the need for strong narratives of change to hold things together for focus, persistence and impact.

The report calls out the role of place and locality. One interviewee in their research noted that “professionalism will be the death of local government. It’s that lack of ability to soften and shape stuff according to locality.”

I was struck too by the report’s constant zig-zagging between what you might call the instrumental skills of the future public service – commercialism, digital and data skills, program and project management and delivery for example – and the more intrinsic values of care and authenticity. “The public service changes that we have set out here,” the report summarises, “in which structures are fragmenting, citizens require authentic interactions, careers require much greater self-management, commerciality and publicness must be reconciled and expectations of leadership are dispersed across the organisation…”

By the by, the concept of “publicness” will probably bear some more thinking in the review of what these reports tells us about the talent set necessary for a modern public service. It hints broadly at a powerful architecture of values and assumptions about holding on to a sense of the value of “public” in the first place – common interests, equity of access, engagement and service and the ability to articulate the distinctive role of public institutions and governance, partly as platform but also as direct and significant player.

This is another good insight into an implicit talent bank that the public servant of the future will need (although some of these skills might make more sense in those public work contexts that are closer to the delivery end in specific locations and communities:

The skill set identified in the co-production literature suggests that it is a combination of more informal roles (‘part good neighbour’) with more formally trained roles (‘part facilitator, part advocate, part support worker’). The expertise for more effective relationships with citizens may well not exist within the corporate centre of the organisation but on the periphery.

The report includes an important warning. “By the time you’ve added up all of the different attributes, capabilities and actual or implied talents necessary for the public servant of the future,” it warns, you are likely to be moving from helpful advice to unhelpful myth-making:

The fleet-of-foot worker, who manages a portfolio career and an emotionally rich engagement with citizens at the same time as exercising personal development and self care, risks being as mythic as the heroic leader who will single-handedly lead an organisation to success. It is of course more likely that attributes will be pooled within teams rather than displayed within one person. The 21st Century Public Servant is a composite role and exists to illuminate a series of working practices rather than to provide a blueprint for a single worker.

The question is how many of these skills and attributes should we expect to find in any one public servant or group of public servants or, more broadly, public purpose workers? How does the skills profile, and its associated talent bundles, change with context including role, geography, and policy and delivery domain? And how useful are the gathering lists and prescriptions for talent as a basis on which to make judgements about recruitment, retention and reward? To what extent would a more determined approach to ‘fixing’ the talent dimension of the public sector fix the larger challenges of the public sector itself, absent complementary shifts in ideology, culture, leadership and day-to-day practice which, in turn, reflect bigger but often unstated assumptions about the wider perception of the public sector’s institutional and instrumental value and contribution?

Final note: a couple of Australian frameworks.

Terry Moran and Chris Eccles were colleagues in the Victorian Department of Premier and Cabinet. Terry went on to head the Prime Minister’s Department in Canberra (and is now Chair of the Centre for Policy Development, on whose Board I also sit) and Chris is now the Secretary of the Premier’s Department in Melbourne, after having done a similar role in South Australia and New South Wales.

Terry’s recent speech about Public Administration 4.0 calls out the same mix of enduring and new skills and capabilities that other studies have picked up. [Public administration 4.0 comes after the Northcote-Trevleyan reforms for a merit-based, impartial public service (1.0), the post-war policy activism and leadership of national policy reform and innovation (2.0), the competition policy reform-driven emphasis on efficiency, separation of policy and delivery and outcomes (3.0)]

“In Australia,” he writes, “I see constant values and culture emphasising the public interest, honesty and the needs of citizens, respect for the authority of elected officials and the parliaments by departments and agencies, a record of solid innovation and creativity in the service of national development, security and community well-being.”

But he’s unequivocal that developing Public Administration 4 as part of the response to digital disruption linked to globalisation is our next big professional task.

The ingredients are increasingly familiar – “big data, open data systems, robotics, artificial intelligence and double digit shifts in productivity will require a further transformation in our workforces, a softening of the boundaries between public and private sector people in any given area of activity and changing community expectations of governments and the public services.”

But always, he argues, “the tested culture and values which guide our work must be preserved and nurtured.”

Being able to pull together that blend of the persistent values of the past with the insistent skills and values of the future is itself rapidly shaping up as a key talent demand for the public service of the future.

The analysis concludes with a rehearsal of 5 principles to guide the evolution of a public administration 4.0:

- Our analytical work needs to be rebalanced to treat distributive justice alongside technical efficiency

- New technologies will make it far easier to devolve more responsibility for delivery to the local level

- …we will need a more strategic approach to planning and assessing investments in our major government systems

- These reforms will be more reliable if we transform our approach to placing planning and management documents before the public

- The public sector should match, if not better, the private sector in responding to new technologies and improving efficiency

Chris Eccles speech about the way the public service might look in 10 years takes as its ‘text’ the fight to eradicate TB, one of the great public service ventures of the past century.

His point is not to suggest we go back to the 1940s. Today’s policy challenges are more complex and the field of public work challenges and priorities more crowded.

But he argues that, like the TB eradication venture, any modern policy endeavour still makes the same basic demands. He suggests that we have to:

- Start with a strong sense of moral purpose

- Have a well-defined and achievable goal

- Utilise all available new technologies

- Get diverse groups of people pursuing the same goals

- Enlist the entire community in the solution.

Ultimately the victory against T.B. shows that good public policy must have a clear picture of the outcomes it wants to achieve. And it must demonstrate how those outcomes will make our lives better.

It’s also worth calling out the admonition that “we join the public service because we care.” “When we’re at our best,” he noted, “it’s because there’s a strong moral purpose to what we do, and good structures in place, motivating us to work for the common good.”

A talent to discern, and then activate, a distinctly moral purpose might not be the first item on many lists of the skill requirements for a modern public service, but it’s likely to strike a chord with those whose chief complaint is that much of our contemporary conversation about the public service lacks sufficient appreciation of the morality and purpose of public work.

It reminds me of the quote from HC “Nugget” Coombs, included in the Victorian 21st century public servant discussion paper I started with:

Beneath the vanities, self-interest and extravagances of any government there is, at least, potentially an element of vision about a juster and more humane society. It is the function of the administrator to recognise that vision and work to give the vision a local habitation.

Coombs H C (1976) ‘The Commission Report’ in Hazelhurst C and Nethercote J R (eds) (1977), Reforming Australian Government: The Coombs Report and Beyond, Royal Institute of Public Administration with Australian National University Press, Canberra, pp4 9–52

Hmmmm …. an interesting and thorough set of reflections Martin … but just where are these super-human individuals to be found?

I was reading today on the work of Carol Dweck, a Professor of Psychology at Stanford University (www.mindsetonline.com). Dweck’s work highlights the difference between fixed and growth mindsets:

“In a fixed mindset, people believe their basic qualities, like their intelligence or talent, are simply fixed traits. They spend their time documenting their intelligence or talent instead of developing them. They also believe that talent alone creates success—without effort.

In a growth mindset, people believe that their most basic abilities can be developed through dedication and hard work—brains and talent are just the starting point. This view creates a love of learning and a resilience that is essential for great accomplishment. Virtually all great people have had these qualities”.

If we subscribe to the view that the public purpose sector is complex and rapidly evolving then the most important attribute of a successful public servant comes down to their ability to get stuff done … to execute policy and service delivery reforms … in order that we may learn what works and what doesn’t.

Increasingly, ‘getting stuff done’ involves delivering through technology. If you can’t deliver through technology (in the second decade of the 21st Century) you can’t get stuff done. Sorry!

Too many public servants display fixed mindsets, grounded in ideology and endless policy debates that are not informed by facts because the ideas are never actually operationalised … or they take so long to be put into practice that the world shifts around them.By the time the ‘grand solution’ arrives the ‘problem’ has moved on.

People with a growth mindset are more motivated to do something useful quickly, learn and then improve on the situation … which is inherently more engaging, effective, adaptive and resilient.

I like the schematic, and of course we need to wear many hats – or build teams of people that can comfortably wear different, complementary, hats – but the bias has to be to people with a growth, learning, mindset that have the skills to execute policy and service delivery reform through technology.

Totally agree Steve…the growth mindset is where we are heading. So we either find such people as an act of deliberate recruitment policy or strategy or we grow such people by nurturing their propensity to learn, try, adapt, learn some more. And they demands a particular style of supportive, demanding and permissuve leadership. So my question is do we see in the public service the kinds of leaders and leadership conducive to this kind of growth mindset?